“In the last half-century, the most popular names given to American children have become less common than ever before.” — the first sentence of my dissertation abstract.

Given the wild popularity of my baby name post from a few weeks ago (61 hits as of today, including 40 unique visitors in one day — eep!), I figured it would be well worth my time to write another post or two on the subject.

Since I started working on my dissertation (in 2009), I’ve had several friends and friends-of-friends who’ve asked me for baby name advice — and although I usually end up offering them more information than they want, my opening line is generally pretty well-received. I tell them that if they want to choose a popular name, they shouldn’t worry about their child being one of three Isabellas or Sophias in her class, because the most popular names aren’t as popular as you’d think.

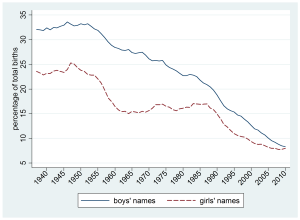

Basically, beginning around WWII, the percentage of kids getting the most popular names began to decline pretty dramatically. In 1940, the #1 most popular names (James and Mary, if you were curious) were given to about 5% of boys and girls born that year; by 2010, the #1 names (Jacob and Isabella) were given to only 1% of kids. You see the same declines in the percentage of kids getting the top ten, top one hundred and top one thousand names; in fact, by 2010, almost 10% of American kids received a name that was given to 5 or fewer kids in the whole country.

A handy graph to explain this (click to embiggen):

Top 10 Most Popular Boys’ and Girls’ Names Nationally as % of Overall Births, 1940-2010*

The percentage of children receiving the top ten most popular American boys’ and girls’ names declined drastically over the latter half of the 20th century.

This graph shows us a few interesting things besides the decreasing percentage of kids receiving top ten names, most notably that popular boys’ names have historically been significantly more concentrated than girls’ names. There are a few things that could explain this, including the fact that parents are more likely to use legacy names (family names) for boys than for girls, and that girls’ names tend to move in and out of fashion more quickly than boys’ names do (between 1880 and 2012, the Social Security top ten lists encompassed 45 boys’ names and 83 girls’ names). However, as you can see, in the last 15 to 20 years, popular boys’ names have finally started to catch up with popular girls’ names in terms of declining density. This suggests that boys’ names might finally be starting to be seen as a “fashion” in the way that girls’ names have been for a long time.

There are a lot of folk explanations you could offer for the declining popularity of popular names: that immigrants to the United States are more inclined to choose “ethnic” names for their kids now than they were in the past, or that parents from different racial backgrounds are increasingly choosing names very different from one another. However, looking at birth certificate data from California, I found evidence suggesting that the trend toward more unique names was present across all demographic groups: regardless of whether I looked specifically at white or black parents, American-born or immigrant parents, or college- or high-school educated parents, I found that those naming babies in the 21st-century were choosing more distinctive names than their counterparts from a few decades before.

This was a surprise to me, not least because, as far as I could tell, no one in the “baby name world” was really talking about it. Popularity rankings are all over the place in the name-o-sphere these days — when I sat down to try to pull together some numbers, I found that almost every book and website I investigated (including most of those I linked to in my previous post as sources for fellow name nerds) included rankings — but no one anywhere pointed out that if you named your son Jacob in 2010, statistically he’d have to be in a classroom with 100 other boys to end up with another Jacob in his class (by comparison, if you were born in 1975 and your name was Jennifer or Michael, statistically you would’ve only needed to be in a group of 25 kids of your gender to have another with your name).

My dissertation attempted to explore the “why” behind this question — why more and more parents are avoiding the most popular names and seeking out distinctive names for their kids instead — and I’ll get to that part in another post. But in the meantime, fellow name nerds, know this: if you’ve always loved the name Sophia (#1 in 2012) or Noah (#4), you should feel free to go ahead and use it. Your kid will certainly meet other people with their name, but the days of Jennifer and Michael (each topping out at over 4% of the population at their peaks) look like they’re gone.

* Data assembled from the Social Security Administration website and the CDC record on numbers of recorded births.

mattllavin

/ May 30, 2013[…]if you were born in 1975 and your name was Jennifer or Michael, statistically you would’ve only needed to be in a group of 25 kids of your gender to have another with your name[…]

From my experience (born in 1976), a group of 25 kids often generated multiple Matthews, though never more than 3 in one class.

Yours truly,

Matt L. (as I was referred to until age 12ish)

LikeLike

diana2261

/ May 31, 2013Well, and this is why statistics don’t tell the whole story 🙂

What I’ve found is that names do tend to cluster geographically (for instance, statistics tell me that if you had been born in the Southeast, your name would’ve been substantially less popular — in the low 20s instead of near or in the top 10) and demographically (especially by race — evidence suggests that’s a stronger sorting mechanism than class, education or just about anything else, that white kids’ names are most likely to be similar to other white kids’ and black kids’ to other black kids’); even among “unique” names, Bay Area kids are more likely to be similar to each other in the KIND of uniqueness their families seek out (lots of word names, for instance).

I taught a preschool religious ed class when I lived in NJ that had 5 students, of which 2 were named Olivia, and I know Olivia’s never reached THAT level of population density 🙂 So some of it is a crapshoot, for sure. But there’s still not anything out there right now that looks the way Jennifer did in the ’70s.

LikeLike